Let’s think about movies like A Clockwork Orange, Columbus, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy or the series The Misfits, The Game and the most recent and award-winning The Brutalist, the movie by Brady Corbet that triumphed at the 2025 Oscars, winning 3 statuettes. It doesn’t take much to understand that Brutalist architecture with its most iconic locations represents a precise aesthetic and stylistic choice that for many filmmakers represents an unconstested added value.

But what characterizes the Brutalist architecture and why has it taken on a leading role in the media?

This is Brutalism in short: the solid and significant volumes, the essential and radical forms, the relatively dystopian character, but above all the exposure of the applied materials in their expressiveness. It is characterized by the use of glass, bricks, stone, steel, exposed systems, and unfinished surfaces, with a particular preference for béton brut, the one that Le Corbusier used in his project for the Unité d’Habitation de Marseille, also known as the Cité Radieuse, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It is an architectural movement with a sometimes annoying beauty, but ethically brave and resilient, with expression of a strong will to affirm a different ‘beauty’.

To understand the synergy that has been established between Brutalism and media let’s try to understand how they met.

Already in 1971, when the movement had not been established for long, we find a milestone in cinema such as Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. The movie, shot in the London district of Thamesmead, had found in some of the Brutalist locations of the 1960s the symbol of an unreasonably violent and completely unresolved contemporary society.

Since then, in addition to cinema, some of the most popular TV series such as Misfits (2009-2013, teen drama with fantasy overtones), winner of a BAFTA award, have taken place in environments with an obvious brutalist design. The production once again took place in Thamesmead, between the suburbs of Greenwhich and Bexley, and proposes the style of béton brut as an icon of a society in which the individual feels alienated and helpless.

In 2014, another very popular series was launched, The Game: a true spy story largely filmed in the Birghingam Central Library, a building designed in 1974 by John Madin. An icon of British Brutalism for its use of concrete, its geometry and its inverted ziggurat shape, this building symbolized the idea of social progress and the optimistic vision. In the TV series, the location becomes a sort of bunker with a run-down aesthetic in which the special committee at the heart of the plot tries to implement a plan against the KGB.

But let’s go back to cinema: in 2011, Tinker Tailor was released in theaters. Director Tomas Alfredson sets his story in London in the early 1970s. Taking place during the Cold War, the task is to expose a Soviet agent at the top of the British secret service who is playing both sides. The movie, which received critical and public acclaim, has as its main location an apparently Victorian-era structure which is actually a brutalist architectural block dating back to the 1960s and digitally inserted into the main courtyard of the building where action takes place. It is between these thick walls of bare concrete that the whole story unfolds and the group of MI6 officers manages to complete the mission to unmask the mole.

Finally we come to the highly acclaimed The Brutalist, (2024), a movie that received positive reviews worldwide. This is the plot in brief: Laszlo Toth, a Hungarian Jewish architect who escaped Buchenwald, arrives in the United States where, with alternating phases, he finds the path to success thanks to a wealthy patron who commissions him to design a large multifunctional building to dedicate to his deceased mother and for which he seems to grant him total creative freedom. For this reason the architect imagines his creation as a large brutalist building, pure and austere in its lines as well as in its material, a concrete metaphor of the horror he experienced first-hand in the concentration camps.

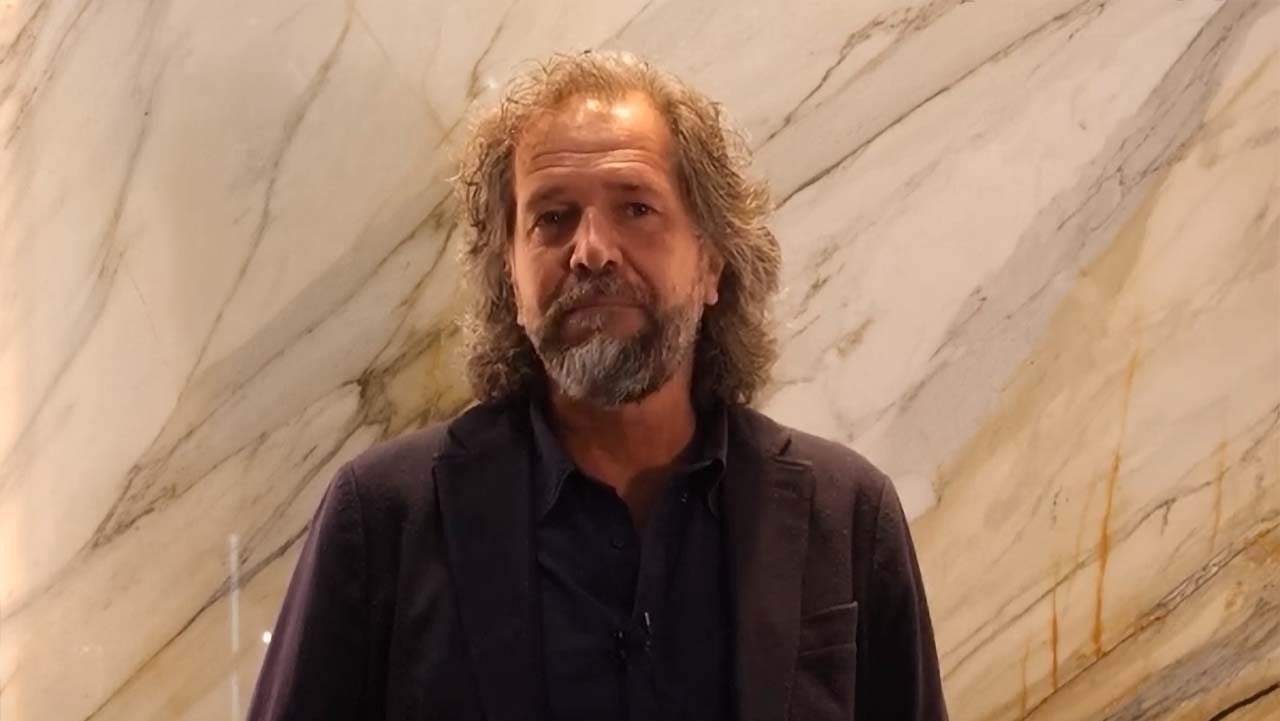

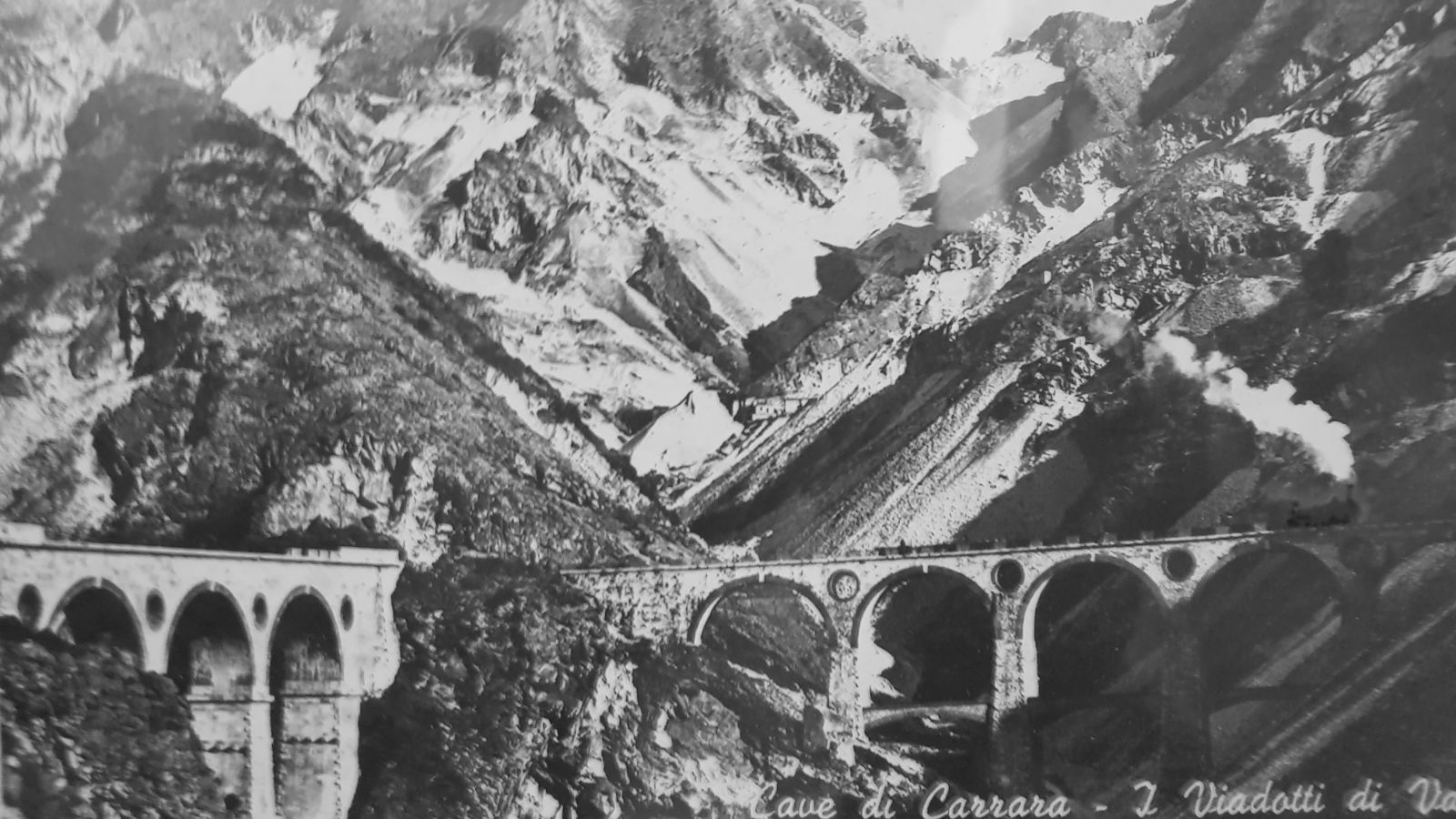

While it is true that the film features an aesthetic and iconography directly linked to the Brutalist architectural movement, it is also true that a good part of the movie is represented as a form of poetic narration of some of the most iconic places in our country, first and foremost the astonishing and unmistakable marble quarries of Carrara, which are majestic from a visual, but also thematic and symbolic point of view. When Toth, not without difficulty, tries to find the right material for his project, he comes across Carrara marble and the quarries: once again the incredible skyline of the Apuan Alps takes centre stage and marble becomes again the architect’s chosen material, renewing that dialogue between man and stone that has always given vision and infinite creative possibilities to architecture. So Elisabetta Caprotti opens her article in Vogue:

Other articles

BLOG

BLOG

Franchi Umberto Marmi hosted thirty-six young architects from the UNC

BLOG

BLOG

FUM Academy: A New Chapter in Marble Education

BLOG

BLOG

Supernatural: Architecture and Marble: a Well-functioning Match

BLOG

BLOG

The Brutalist: Adrien Brody in the Carrara Quarries - In theaters from January 23 2025

BLOG

BLOG

FUM ACADEMY: PEOPLE AND KNOWLEDGE AT THE CENTER

BLOG

BLOG

Stories: Carrara Marble for the Freedom Tower

BLOG

BLOG

Lizzatura storica - Ponti di Vara

BLOG

BLOG

We are nature. The sustainability of the Natural Stone at Fuorisalone 2023

BLOG

BLOG

Sustainability and technology, the management of water resources

BLOG

BLOG

From "Essere Marmo", the Carrara marble sustainability manifesto, "Marble narrates"

BLOG

BLOG

The luxury and sustainability of marble even "on board"

BLOG

BLOG

Marble Architecture: discovering MAMAC – Modern and Contemporary Art Museum of Nice

BLOG

BLOG

The FUM headquarters expands: the new hall C1

BLOG

BLOG

Openbox Architects designs with marble and integrates architecture with the landscape: the Marble House in Thailand

BLOG

BLOG

Eros table by Angelo Mangiarotti

BLOG

BLOG

Fili Pari: marble dust become fabric

BLOG

BLOG